Table of Contents

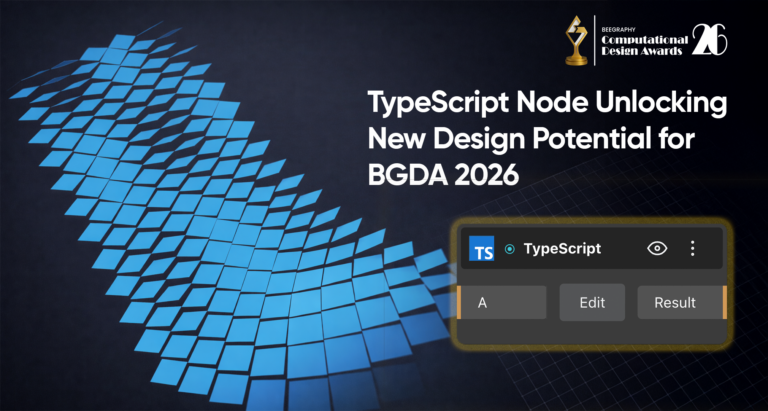

Parametric design is where creativity and logic meet. For most designers, particularly for those who work with computational workflows, BeeGraphy might be a good starting point into this world. Its visual node system provides an insight into the way more complex processes can be more comprehensible, but clearly link up parameters with form. However, as designers may become more ambitious, there soon arises the necessity for something much more organized yet expressive. In this respect, the TypeScript node stands at the forefront: as the link between visual design and algorithmic control, enabling projects that are truly scalable, flexible, and highly parametric.

This article explains why the TypeScript node matters, what it brings to BeeGraphy’s visual methodology, how AI systems such as Claude can accelerate code-driven workflows, and how those concepts interrelate through the metaphor of a parametric bench. The tone is considerate and lucid, consistent with the style of the BeeGraphy blog and focused on design thinking rather than technical explanation or coding. You should have more than just an idea of what can be done with the TypeScript node by the end but also an understanding of how it furthers the designer’s creative process.

Why Code Matters Inside a Visual Platform

At first glance, adding TypeScript to a visual platform may appear to be a contradiction. If the goal is accessibility, then why add code at all? The answer comes down to balance. The advantages of visual systems are unparalleled when it comes to expressing spatial relationships and intuitive workflows. They are clean, immediate and readable. But they become less efficient when a project requires repetition, logic branching or structured data.

The TypeScript node extends the node system by providing a place where logic can be programmed succinctly and exactly. It extends, rather than replaces, the visual pipeline. For example, a designer might want to create node-based layouts for previews or high-level operations and then use TypeScript for specific tasks that require organization and abstraction. This hybrid approach honors intuition and structure.

Furthermore, adding code to BeeGraphy doesn’t require you to become a software engineer, but to use one more tool. As your ideas get more complicated you will want to choose the best way to express each part of your design. And when designers do this, with practice, it’s quite normal for them to switch between purely visual and code-based thinking.

When Node Graphs Become Unwieldy

On smaller projects, node graphs stay efficient and clear. With growing complexity, though, you start to notice patterns: clusters of nodes repeated repeatedly, multiple branches for trees that should be copied when modifying it, a long chain of nodes to indirectly represent loops or conditions. These generate cognitive overhead. You may be doing more graph wrangling than developing your design.

The TypeScript node frees you from that burden. Instead of duplicating logic throughout the graph, you centralize it. Instead of creating long chains of operations for repeated elements, you programmatically generate them. And instead of visually branching for every design variation, you concisely express conditions.

This, in turn, makes your project more maintainable. If you want to change one aspect of the logic, you change it once in code rather than in multiple node clusters. In addition, this will keep your graph visually clean and easier to understand by others for further modification.

Conveying Reason in a precise manner

In essence, code lets you express things, which are hard and sometimes impossible to describe with nodes. Imagine doing things like distributing points along a variable path, calculating spacing that adapts to user input conditionally, reorganizing data, and auto-generating mirrored geometry. These are straightforward in code but would take large node structures to achieve visually.

Code brings precision to these ideas. You define mathematical relationships directly, you manage arrays of geometry, and you enforce constraints. You build helper logic once and reuse it throughout the project. Rather than scattering logic throughout the graph, you structure it in a tidy script.

This level of precision enables designers to engage in projects that they might otherwise shun because of visual complexity. It turns BeeGraphy into a platform where conceptual exploration can scale without becoming messy.

How AI Tools Boost Code-Based Workflows

Coding can feel intimidating for many designers, but AI and visual tools make the transition far more approachable. The biggest barriers are usually syntax and structure, not the logic itself. Designers already understand patterns intuitively, they just hesitate when asked to express them in code.

- Large language model AI tools like Claude.ai act as cooperative partners that convert natural language into workable starter logic.

- This removes the pressure of writing every line from scratch and gives designers a clear foundation to build on.

- AI does not replace understanding, it accelerates iteration by handling repetitive and error-prone parts of coding.

- Designers remain fully in control, testing, refining, and shaping the logic and geometry themselves.

- In this role, AI becomes an extension of sketching, helping designers think through logic the same way nodes help visualize form.

- With both nodes and TypeScript available, designers shift into a more strategic space, focusing on relationships, rules, and systems.

- This mirrors the direction of computational design, where designers orchestrate dynamic systems rather than craft isolated objects.

- Automating structure frees up creative bandwidth, enabling fast variation, extreme experiments, and entire families of designs.

- Designers become the choreographers of performance, setting rules that the system executes, and BeeGraphy supports this through intuitive visual tools combined with structured scripting.

Parametric bench using Typescript and Claude

A parametric bench in BeeGraphy can be generated entirely through TypeScript, with Claude helping write and refine the logic behind the geometry. This tutorial walks through how to script the bench from scratch, build its structure through curves and solids, and control the overall form through code rather than manual modeling. You will see how BeeGraphy’s geometry classes and solid tools can be combined with Claude’s code generation to create a fully parametric, customizable bench that updates instantly whenever the script changes.

TypeScript in Beegraphy

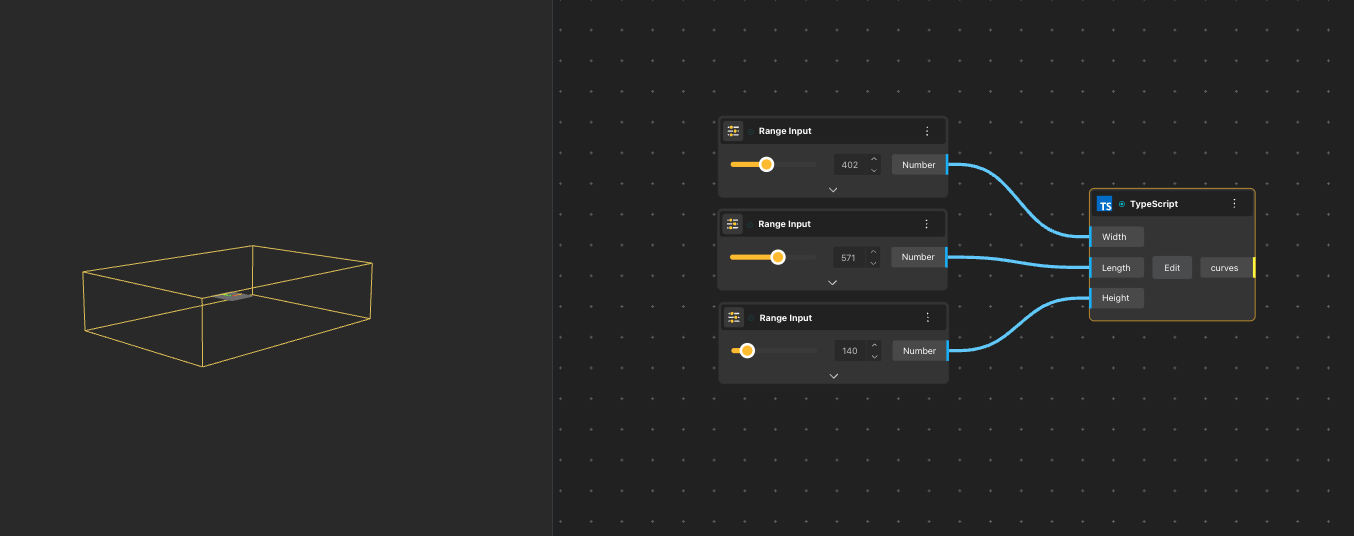

Step 1: Open the BeeGraphy Editor, double click and add a TypeScript node to your canvas.

Step 2: Copy the code you want to use and paste it into the script by clicking the Edit button on the node.

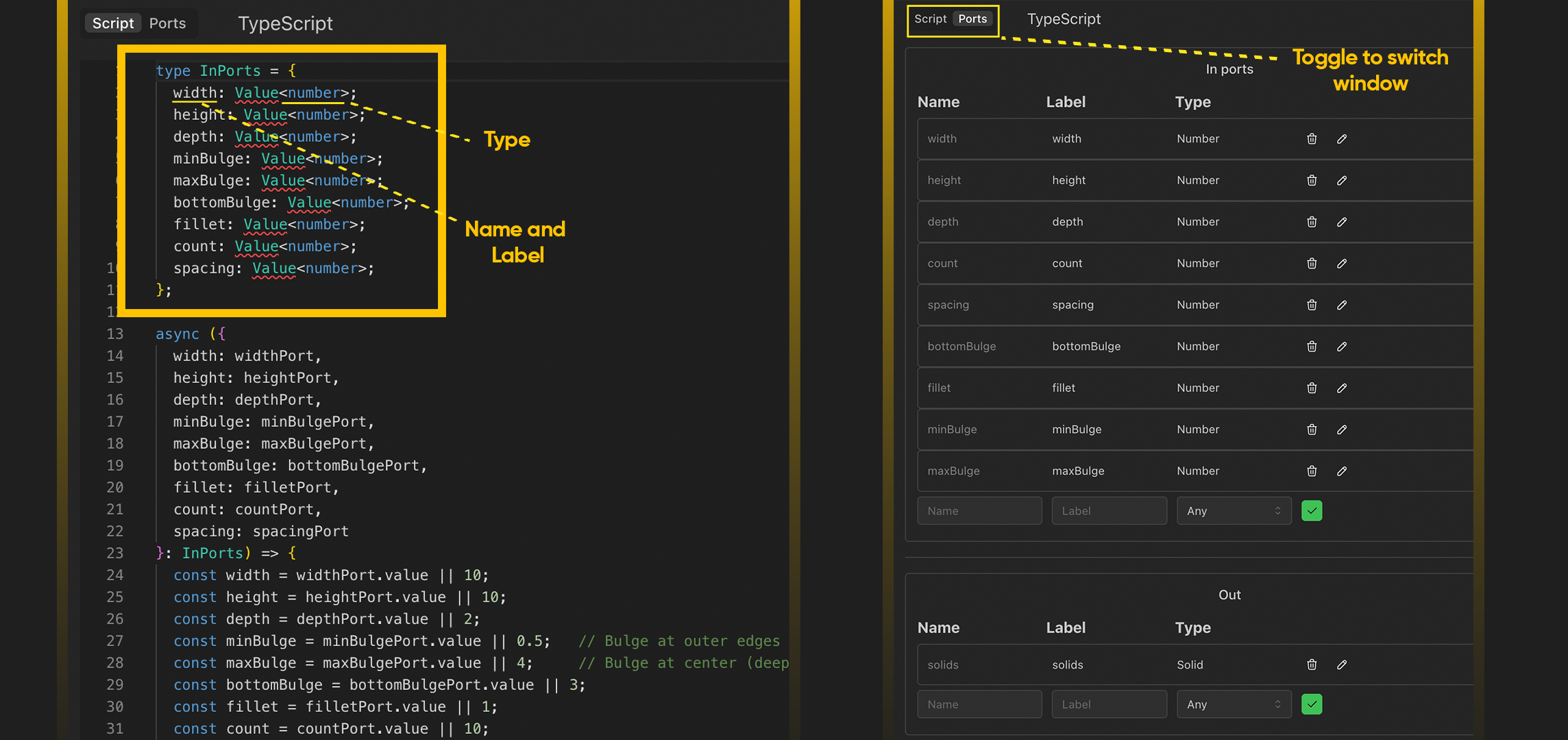

Step 3: Inside the window, click Ports in the top left corner. Delete all the default input and output ports.

Step 4: At the top of your code, you will see the in-port names and their types. Copy each name into the Ports panel and assign the correct type in the drop down menu (scroll to find the desired one). This is important for the node to work properly.

Step 5: Scroll to the bottom of the code to find the out port name, such as curves, surfaces, or solid. Copy that into the output ports and select the matching type.

Prompting Claude

Claude does not generate BeeGraphy ready code directly, so we go step by step.

Step 1: In this case, we asked Claude to make a rectangle by giving it two additional things: the BeeGraphy guide links and a sample code. Providing both of these things are important in order to make claude aware of the Beegraphy classes and the A Sample code structure.

Beegraphy Classes

The Curve Class is a fundamental component within our system, representing a geometric curve. It encapsulates the properties and methods needed to define and manipulate curves in various forms.

The CurveBuilder Class is designed to simplify the process of constructing curves. It offers a set of static methods that facilitate the creation of various types of curves by providing an intuitive and flexible interface.

The FontBuilder Class is a powerful tool for constructing fonts and generating geometric representations of text.

The Plane Class represents a geometric plane in three-dimensional space. It provides a foundational structure for defining, manipulating, and performing operations on planes, which are essential elements in many geometric and computational tasks.

The Vector Class represents a vector in three-dimensional space, providing a fundamental framework for handling vector operations and calculations.

The Solid Class represents a three-dimensional solid within the application, providing a comprehensive framework for defining, manipulating, and performing operations on solid shapes.

The SolidBuilder Class provides a set of static methods for creating a variety of solid shapes with ease.

The Surface Class represents a surface geometry within the application, providing a robust framework for defining, manipulating, and analyzing surface shapes in three-dimensional space.

The SurfaceBuilder Class offers a range of static methods for constructing surfaces using various algorithms and operations.

The Transformation Class represents a transformation in three-dimensional space, providing a comprehensive framework for applying geometric transformations to objects.

Prompt: Review the BeeGraphy docs and sample code, then help me generate optimized TypeScript node logic for creating a Tapered Box Geometry in BeeGraphy.

Beegraphy Docs link:

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/Geometry

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/Curve

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/CurveBuilder

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/FontBuilder

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/Plane

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/Vector

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/Solid

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/SolidBuilder

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/Surface

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/SurfaceBuilder

https://beegraphy.com/guide/classes/Transformation

// ===== SIMPLE BOX =====

type BoxInPorts = {

width: Value<number>; //Inport Name width

height: Value<number>; //Inport Name height

depth: Value<number>; //Inport Name depth

};

async ({ width: widthPort, height: heightPort, depth: depthPort }: BoxInPorts) => {

const width = widthPort.value;

const height = heightPort.value;

const depth = depthPort.value;

const hw = width / 2;

const hh = height / 2;

const hd = depth / 2;

// Create box vertices

const vertices = [

new Vector([-hw, -hh, -hd]), // 0

new Vector([+hw, -hh, -hd]), // 1

new Vector([+hw, -hh, +hd]), // 2

new Vector([-hw, -hh, +hd]), // 3

new Vector([-hw, +hh, -hd]), // 4

new Vector([+hw, +hh, -hd]), // 5

new Vector([+hw, +hh, +hd]), // 6

new Vector([-hw, +hh, +hd]) // 7

];

const edgePairs = [

[0, 1], [1, 2], [2, 3], [3, 0],

[4, 5], [5, 6], [6, 7], [7, 4],

[0, 4], [1, 5], [2, 6], [3, 7]

];

const edges = await Promise.all(

edgePairs.map(([start, end]) =>

CurveBuilder.polyline([vertices[start], vertices[end]])

)

);

const curves = edges.map((edge) => ({

type: Type.Curve,

value: edge,

meta: { color: "#00aaff" }

}));

return { curves }; //OutPort Name and type

};

Sample code gives creates a simple Box OUTPUT made of curves

Troubleshooting:

- If you see the code is stuck in task execution, remind the chatbot to use await, async & promise . This allows your code to handle asynchronous tasks and won’t get stuck in a loop.

- If you see type error in node after changing the in and out port names, refresh the page and it usually disappears.

- If you encounter other errors in node, such as calling undefined classes, then you can take a screenshot of the error and share it with claude.

- You can also reach out to us on discord in case you need help.

If you are able to generate a working code for a tapered box then Congratulations! We will move to next steps and play with generating geometries using different methods and more complex prompting.

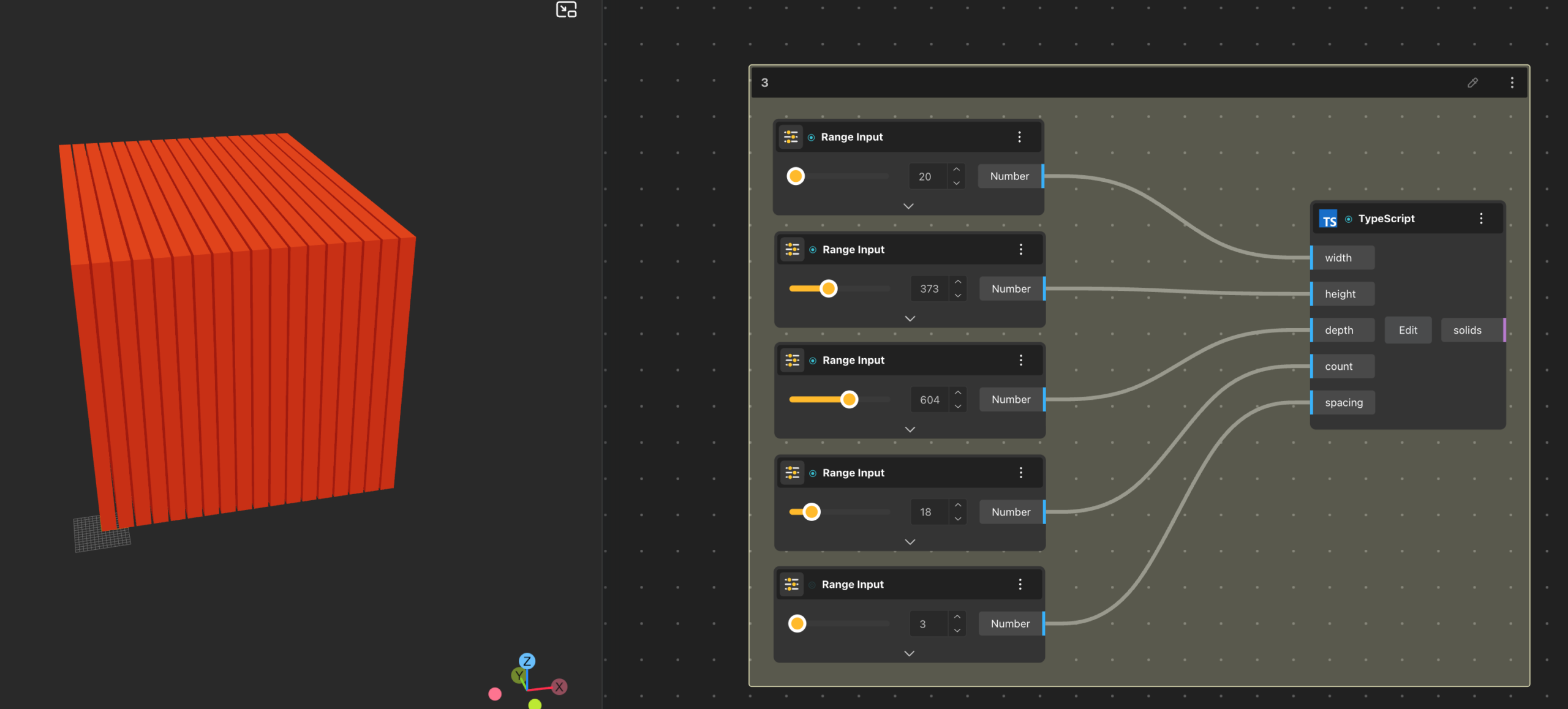

STEP 2: Creating a geometry with lofted surfaces and using Array to repeat the geometries

Note: You can try different prompts to create these geometries. In this case we have created these array of boxes using surfaces as output, however you may prompt to output as Solids as well

PROMPT: Create an array of lofted surfaces along the Y axis using BeeGraphy TypeScript. Each surface should have an hourglass/concave profile created by lofting between 3 horizontal curves:

Bottom curve – a straight horizontal line at z=0

Middle curve – a horizontal line at z=height/2, but narrower (bulged inward) on both sides

Top curve – a straight horizontal line at z=height

type InPorts = {

width: Value<number>;

height: Value<number>;

depth: Value<number>;

bulge: Value<number>;

count: Value<number>;

spacing: Value<number>;

loftDegree: Value<number>;

};

async ({

width: widthPort,

height: heightPort,

depth: depthPort,

bulge: bulgePort,

count: countPort,

spacing: spacingPort,

loftDegree: loftDegreePort

}: InPorts) => {

const width = widthPort.value;

const height = heightPort.value;

const depth = depthPort.value;

const bulge = bulgePort.value;

const count = countPort.value;

const spacing = spacingPort.value;

const loftDegree = loftDegreePort.value;

const hw = width / 2;

const step = depth + spacing;

const surfaces = [];

for (let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

const yPos = i * step;

const middleHW = hw - bulge;

// FRONT SURFACE

const frontBottom = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hw, yPos, 0]),

new Vector([hw, yPos, 0])

);

const frontMiddle = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-middleHW, yPos, height / 2]),

new Vector([middleHW, yPos, height / 2])

);

const frontTop = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hw, yPos, height]),

new Vector([hw, yPos, height])

);

const frontSurface = await SurfaceBuilder.loft(

[frontBottom, frontMiddle, frontTop],

loftDegree

);

// BACK SURFACE

const backBottom = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hw, yPos + depth, 0]),

new Vector([hw, yPos + depth, 0])

);

const backMiddle = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-middleHW, yPos + depth, height / 2]),

new Vector([middleHW, yPos + depth, height / 2])

);

const backTop = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hw, yPos + depth, height]),

new Vector([hw, yPos + depth, height])

);

const backSurface = await SurfaceBuilder.loft(

[backBottom, backMiddle, backTop],

loftDegree

);

// LEFT SIDE SURFACE

const leftBottom = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hw, yPos, 0]),

new Vector([-hw, yPos + depth, 0])

);

const leftMiddle = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-middleHW, yPos, height / 2]),

new Vector([-middleHW, yPos + depth, height / 2])

);

const leftTop = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hw, yPos, height]),

new Vector([-hw, yPos + depth, height])

);

const leftSurface = await SurfaceBuilder.loft(

[leftBottom, leftMiddle, leftTop],

loftDegree

);

// RIGHT SIDE SURFACE

const rightBottom = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([hw, yPos, 0]),

new Vector([hw, yPos + depth, 0])

);

const rightMiddle = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([middleHW, yPos, height / 2]),

new Vector([middleHW, yPos + depth, height / 2])

);

const rightTop = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([hw, yPos, height]),

new Vector([hw, yPos + depth, height])

);

const rightSurface = await SurfaceBuilder.loft(

[rightBottom, rightMiddle, rightTop],

loftDegree

);

// BOTTOM FACE

const bottomFace = await SurfaceBuilder.surface4Pnt(

new Vector([-hw, yPos, 0]),

new Vector([hw, yPos, 0]),

new Vector([hw, yPos + depth, 0]),

new Vector([-hw, yPos + depth, 0])

);

// TOP FACE

const topFace = await SurfaceBuilder.surface4Pnt(

new Vector([-hw, yPos, height]),

new Vector([hw, yPos, height]),

new Vector([hw, yPos + depth, height]),

new Vector([-hw, yPos + depth, height])

);

surfaces.push(

{ type: Type.Surface, value: frontSurface, meta: { color: "#ff5500" } },

{ type: Type.Surface, value: backSurface, meta: { color: "#ff5500" } },

{ type: Type.Surface, value: leftSurface, meta: { color: "#ff5500" } },

{ type: Type.Surface, value: rightSurface, meta: { color: "#ff5500" } },

{ type: Type.Surface, value: bottomFace, meta: { color: "#ff5500" } },

{ type: Type.Surface, value: topFace, meta: { color: "#ff5500" } }

);

}

return { surfaces };

};

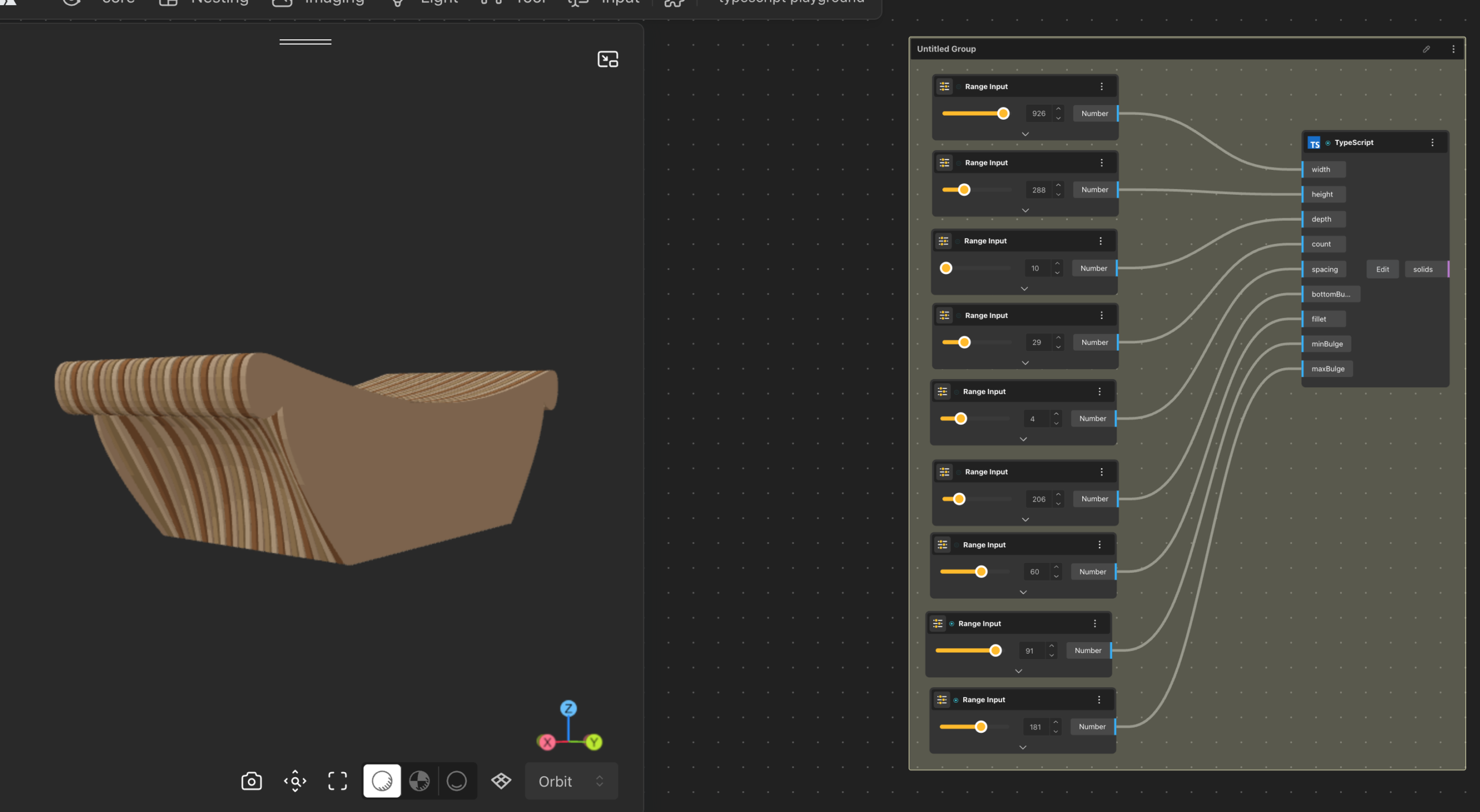

STEP 3: Altering geometry to make a bench

After Step 2, we did not try to get everything in one shot. We prompted Claude for each action separately, in this order:

-

Create the bulges.

-

Scale the bottom face.

-

Apply fillet edges.

Each prompt built on the previous output. Run one change, review the geometry, then give the next prompt. This avoids conflicts and gives you control over the parameters at every stage.

Click here to checkout the Claude.ai chat of this model for reference.

type InPorts = {

width: Value<number>;

height: Value<number>;

depth: Value<number>;

minBulge: Value<number>;

maxBulge: Value<number>;

bottomBulge: Value<number>;

fillet: Value<number>;

count: Value<number>;

spacing: Value<number>;

};

async ({

width: widthPort,

height: heightPort,

depth: depthPort,

minBulge: minBulgePort,

maxBulge: maxBulgePort,

bottomBulge: bottomBulgePort,

fillet: filletPort,

count: countPort,

spacing: spacingPort

}: InPorts) => {

const width = widthPort.value || 10;

const height = heightPort.value || 10;

const depth = depthPort.value || 2;

const minBulge = minBulgePort.value || 0.5;

const maxBulge = maxBulgePort.value || 4;

const bottomBulge = bottomBulgePort.value || 3;

const fillet = filletPort.value || 1;

const count = countPort.value || 10;

const spacing = spacingPort.value || 3;

const hw = width / 2;

const hwBottom = hw - bottomBulge;

// Wood color variations

const woodColors = [

"#C9AC8C",

"#B89B72",

"#D4B896",

"#A67C52"

];

const solids = [];

for (let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

const offsetY = i * (depth + spacing);

const color = woodColors[i % woodColors.length];

// concave bulge calculation

const centerIndex = (count - 1) / 2;

const distanceFromCenter = Math.abs(i - centerIndex);

const maxDistance = centerIndex;

const t = maxDistance > 0 ? distanceFromCenter / maxDistance : 0;

const bulge = minBulge + (maxBulge - minBulge) * (1 - t * t);

const hwMiddle = hw - bulge;

// front profile

const bottomFront = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hwBottom, offsetY, 0]),

new Vector([hwBottom, offsetY, 0])

);

const middleFront = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hwMiddle, offsetY, height / 2]),

new Vector([hwMiddle, offsetY, height / 2])

);

const topFront = await CurveBuilder.bSplineCurve([

new Vector([-hw + fillet, offsetY, height - fillet]),

new Vector([-hw, offsetY, height - fillet]),

new Vector([-hw, offsetY, height]),

new Vector([-hw + fillet, offsetY, height]),

new Vector([hw - fillet, offsetY, height]),

new Vector([hw, offsetY, height]),

new Vector([hw, offsetY, height - fillet]),

new Vector([hw - fillet, offsetY, height - fillet])

], 2, false);

const frontSurface = await SurfaceBuilder.loft(

[bottomFront, middleFront, topFront], 2

);

// back profile

const bottomBack = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hwBottom, offsetY + depth, 0]),

new Vector([hwBottom, offsetY + depth, 0])

);

const middleBack = await CurveBuilder.line(

new Vector([-hwMiddle, offsetY + depth, height / 2]),

new Vector([hwMiddle, offsetY + depth, height / 2])

);

const topBack = await CurveBuilder.bSplineCurve([

new Vector([-hw + fillet, offsetY + depth, height - fillet]),

new Vector([-hw, offsetY + depth, height - fillet]),

new Vector([-hw, offsetY + depth, height]),

new Vector([-hw + fillet, offsetY + depth, height]),

new Vector([hw - fillet, offsetY + depth, height]),

new Vector([hw, offsetY + depth, height]),

new Vector([hw, offsetY + depth, height - fillet]),

new Vector([hw - fillet, offsetY + depth, height - fillet])

], 2, false);

const backSurface = await SurfaceBuilder.loft(

[bottomBack, middleBack, topBack], 2

);

const solid = await SolidBuilder.loft(

[frontSurface, backSurface], 1

);

solids.push({

type: Type.Solid,

value: solid,

meta: { color }

});

}

return { solids };

};Click here to checkout the Beegraphy file with TypeScript code

Why this matters for the future of computational designers

The design industry is shifting toward the use of parametric, generative, and adaptive systems throughout architecture, furniture, products, and interfaces. Being able to think and work in a parametric way is becoming a crucial skill. BeeGraphy offers a space where designers can begin this journey without being overwhelmed.

The TypeScript node does not intend to make this platform more complex; instead, it empowers those designers needing more. It supports a smooth transition from visual to structural logic. It builds confidence in designers to take on bigger and even more complex projects. It actually prepares them for workflows practiced in professional computational design studios.

Merging nodes, TypeScript, and AI assistance reflects how many real-world design teams are used to working. It reflects an understanding that creativity does not come from tools in isolation, but from how well you use them together.

Conclusion

The new BeeGraphy TypeScript node represents a significant extension of what is possible in a cloud-based parametric design platform. It gives designers the power to express intricate, beautiful logic and retains strong visual strengths in node-based modelling. AI tools bridge the gap for beginners and enable fast drafting and iteration.

The idea of the parametric bench shows how this hybrid workflow brings clarity and flexibility to design. A simple object becomes a rich system, a single idea many variations, and the designer is free to explore without being held back by manual work.

It encourages designers to think in relationships, patterns, and behavior. Ultimately, the TypeScript node opens the door to a deeper practice of computational design, where logic and creativity move together. This is the future of parametric design, and BeeGraphy gives designers the tools to step into it with confidence.