Table of Contents

At the intriguing nexus of mathematics, nature, and design are fractals. At first glance, they seem complicated and occasionally overwhelming, but they are actually based on surprisingly straightforward rules. When you comprehend how fractals function, you start to see them everywhere—in plants, clouds, snowflakes, shells, coastlines, and even structural and architectural systems.

Fractals are particularly captivating because their intricacy is not created by hand. Rather, it appears. Emergence is a fundamental concept in both computational design and natural systems.

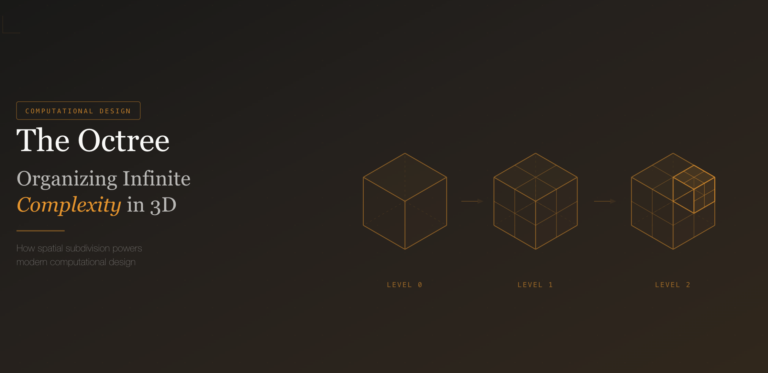

How Fractals Operate

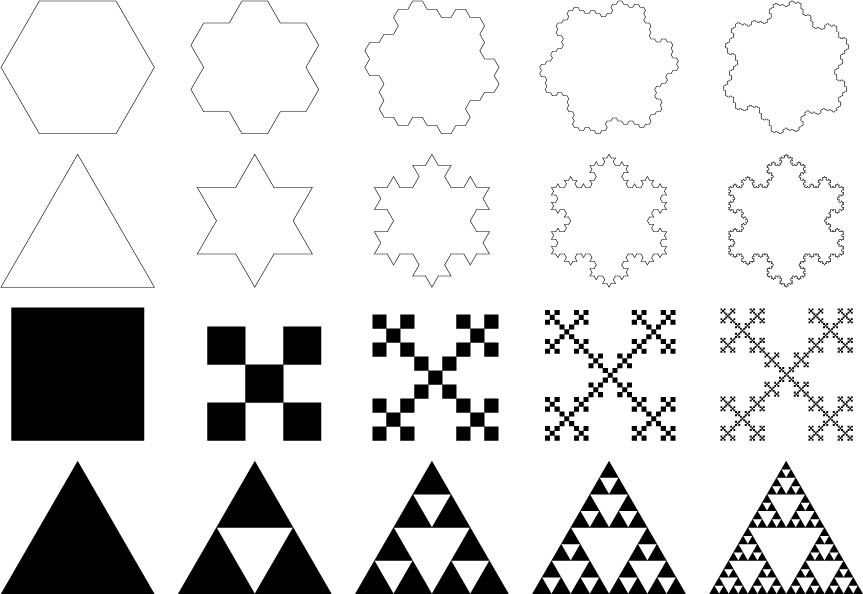

A shape made by repeatedly performing the same operation is called a fractal. Rather than directly modeling a complex form, you establish three essential elements:

- A fundamental geometry

- A rule that modifies this geometry

- Several iterations

The same rule is applied to the outcome of each iteration. Over time, repetition leads to the natural emergence of complexity.

Self-similarity is the key concept of fractals. It shows that despite the variations in the size level, there are similarities between the configurations and the larger shapes in the patterns. The same principles are usually repeated when you zoom in on the shapes of fractals.”

Self-similarity may be:

- Exact, in which the shapes repeat exactly

- Approximate, with the same rule applying, although the results are slightly different.

This is why the fractal is very useful in the explanation of natural phenomena, where the outcome is never perfectly uniform, but follows certain rules.

Such an understanding resonates with parametric and generative designs that depend on relationships and rules to define shapes rather than geometry.

How to Create a Fractal

Fractals usually begin with a singular instance of the shape or pattern of your choice. A rule is applied for the transformation and with each iteration the instances grow exponentially, here are the steps in detail.

1. The Base Geometry (Seed)

Every fractal starts with a simple shape, often called the seed or initiator.

This could be:

-

A line

-

A triangle

-

A square

-

A point

At this stage, the geometry is deliberately uncomplicated. The power of fractals does not come from the starting shape but from what happens after.

2. The Transformation Rule

Next comes the most important part: the rule.

The rule defines how the base geometry should be transformed. Common transformations include:

-

Scaling the shape down

-

Splitting it into multiple parts

-

Rotating or translating copies

-

Removing specific sections

This rule is applied consistently and precisely. The rule does not change between iterations.

3. Iteration (Repeating the Rule)

Once the rule is defined, it is applied again, not to the original shape, but to the result of the previous step.

Each iteration repeats the exact same transformation:

-

Iteration 1 applies the rule to the seed

-

Iteration 2 applies the rule to all new shapes

-

Iteration 3 applies the rule again, and so on

This repetition is what creates exponential growth in detail.

4. Self-Similarity Across Scales

One of the defining features of fractals is self-similarity.

This means:

-

Small parts of the shape resemble the whole

-

Zooming in reveals the same structure repeating

-

The pattern remains recognizable at different scales

5. Controlled Complexity

An important point is that fractals are not infinite in practical design tools. They are bounded by iteration count.

By controlling:

-

Number of iterations

-

Scale factor

-

Rotation or spacing

You control how complex the fractal becomes. This is why fractals work so well in parametric design environments like BeeGraphy. A single slider can dramatically alter the outcome.

Why Fractals Matter for Designers

Fractals are not just mathematical curiosities. They teach a way of thinking that is essential for computational design:

-

Designing systems instead of single objects

-

Letting rules generate form

-

Controlling complexity through parameters

-

Understanding how small changes affect large outcomes

For designers working with BeeGraphy, fractals strengthen how you approach nodes, lists, transformations, and code. They encourage you to think procedurally rather than visually alone.

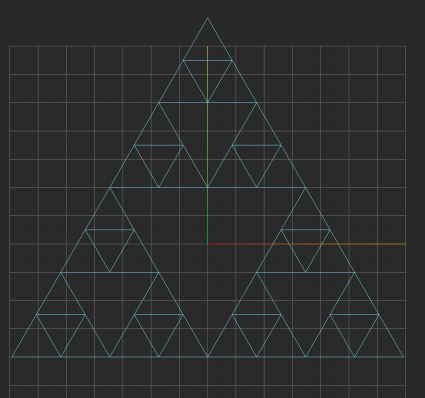

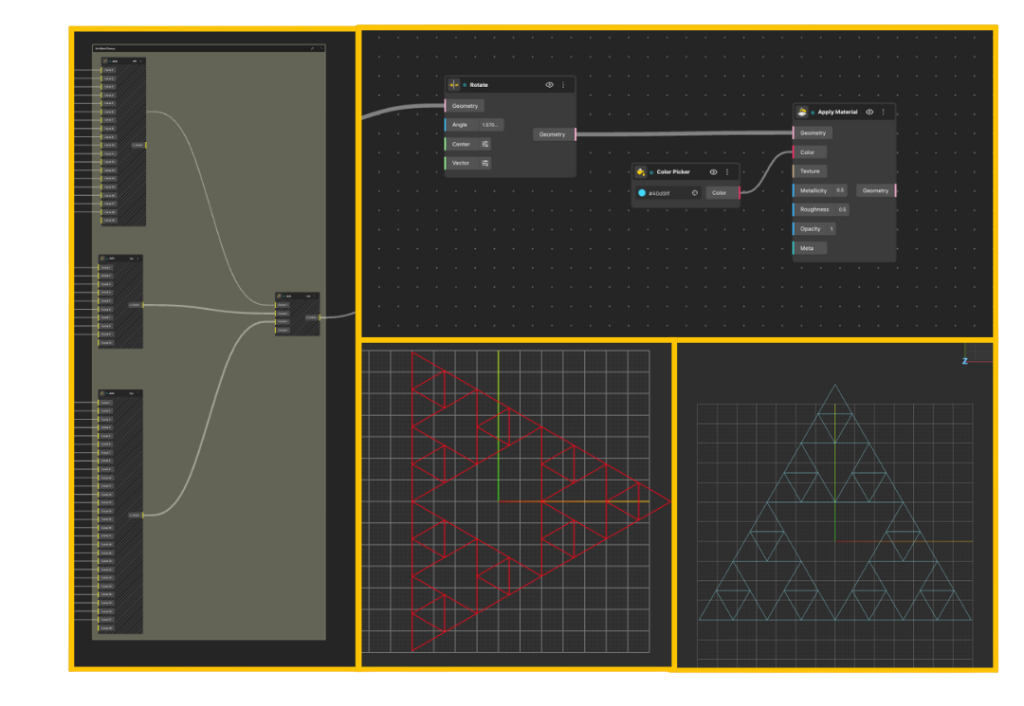

Method 1: Creating Fractals Using Nodes

This node-based fractal workflow follows a clear, repeatable structure. Instead of using abstract repeat nodes, the fractal is built explicitly through geometric decomposition and reconstruction at each iteration. This makes the logic transparent and easy to debug.

The example shown here constructs a triangle-based fractal, similar to a Sierpiński pattern.

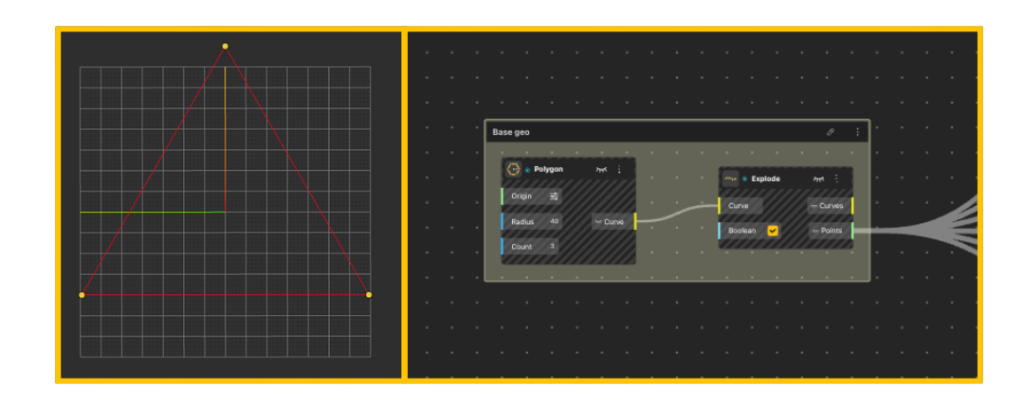

Step 1: Define the Base Geometry

We begin by defining a single, minimal parent shape.

-

A Polygon node is used to generate the base geometry

-

The polygon Count is set to 3, producing a triangle

-

The Radius defines the overall scale of the system

This triangle acts as iteration zero, the root geometry for the entire fractal.

Immediately after:

-

The triangle is passed into an Explode node

-

The output gives us:

-

Individual edge curves

-

The triangle vertices as points

-

These extracted points become the data source for all subsequent construction.

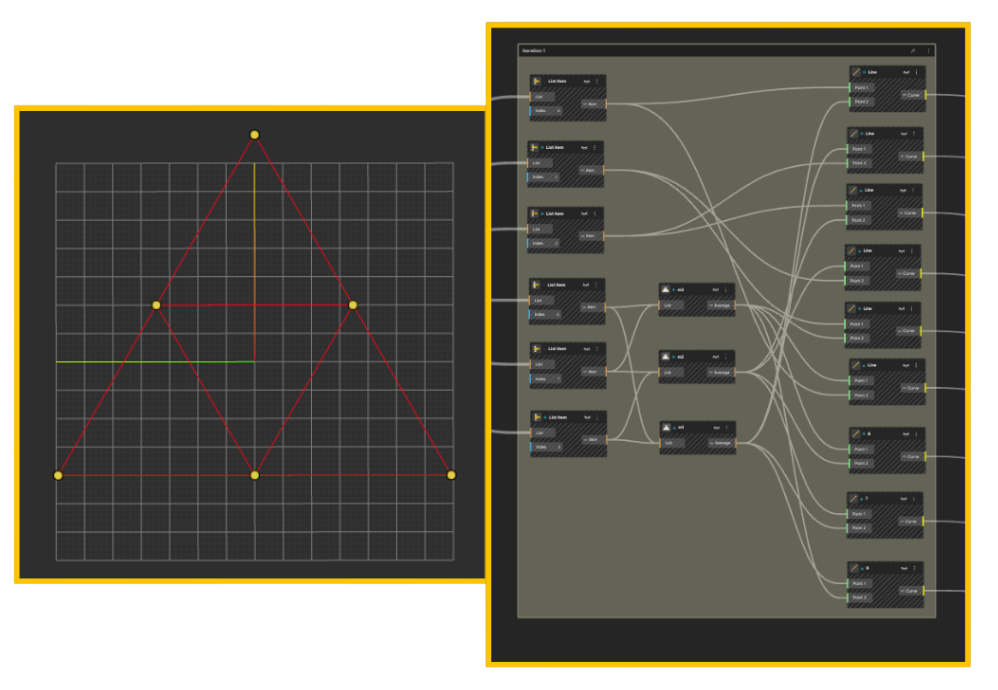

Step 2: Iteration 1, Subdivide the Triangle

The first iteration focuses on rebuilding geometry from derived points rather than transforming the original triangle.

Midpoint calculation

-

Each edge is connected to a Midpoint node

-

This produces one midpoint per edge

At this stage:

-

We are not scaling geometry

-

We are reconstructing new geometry using derived points

Rebuilding edges

-

Line nodes are used to connect:

-

Original vertices

-

Computed midpoints

-

This results in:

-

Smaller internal triangles

-

A clear triangular hierarchy forming inside the parent shape

This completes Iteration 1.

Step 3: Iteration 2, Repeat the Same Logic

Iteration 2 introduces no new logic.

-

The exact same node structure from Iteration 1 is reused

-

Each triangle generated previously is treated as a new parent

For each new triangle:

-

Midpoints are calculated using Midpoint nodes

-

Points are reconnected using Line nodes

This repetition is what defines the fractal.

The node graph grows wider not because the logic changes, but because the same logic is applied to an increasing amount of geometry.

.

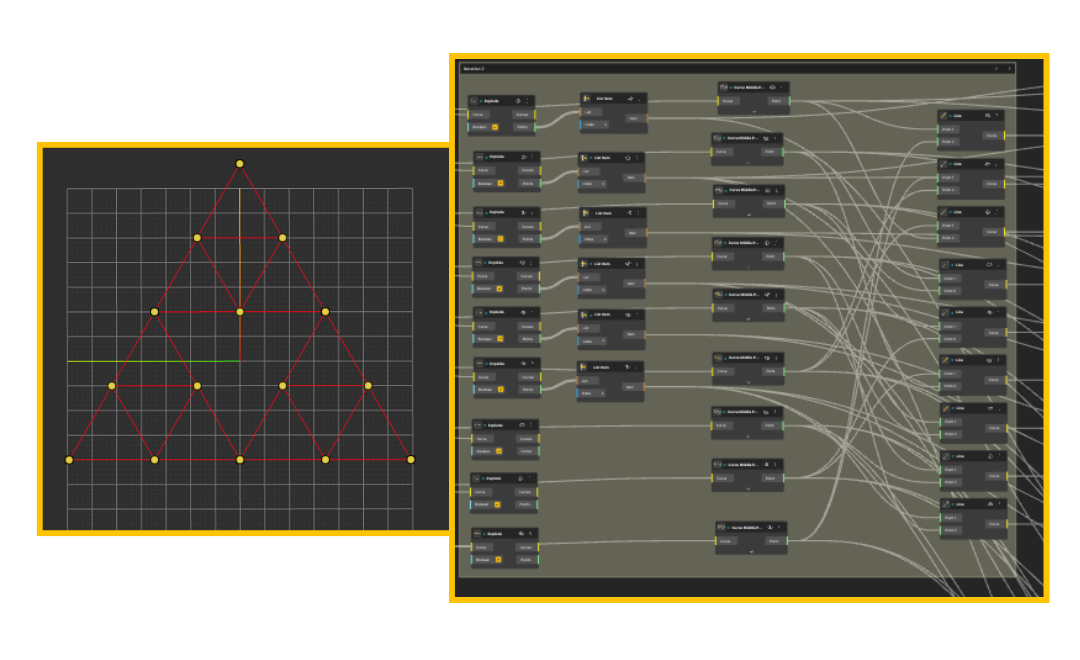

Step 4: Managing Growth Through Grouping

As iterations increase, organization becomes critical.

-

Each iteration is placed inside its own Group

-

Groups are labeled clearly by iteration number

-

Inputs and outputs remain consistent across groups

This mirrors how fractals behave conceptually:

-

Same rule

-

Same structure

-

Increasing complexity through repetition

Grouping keeps the graph readable and prevents exponential visual clutter.

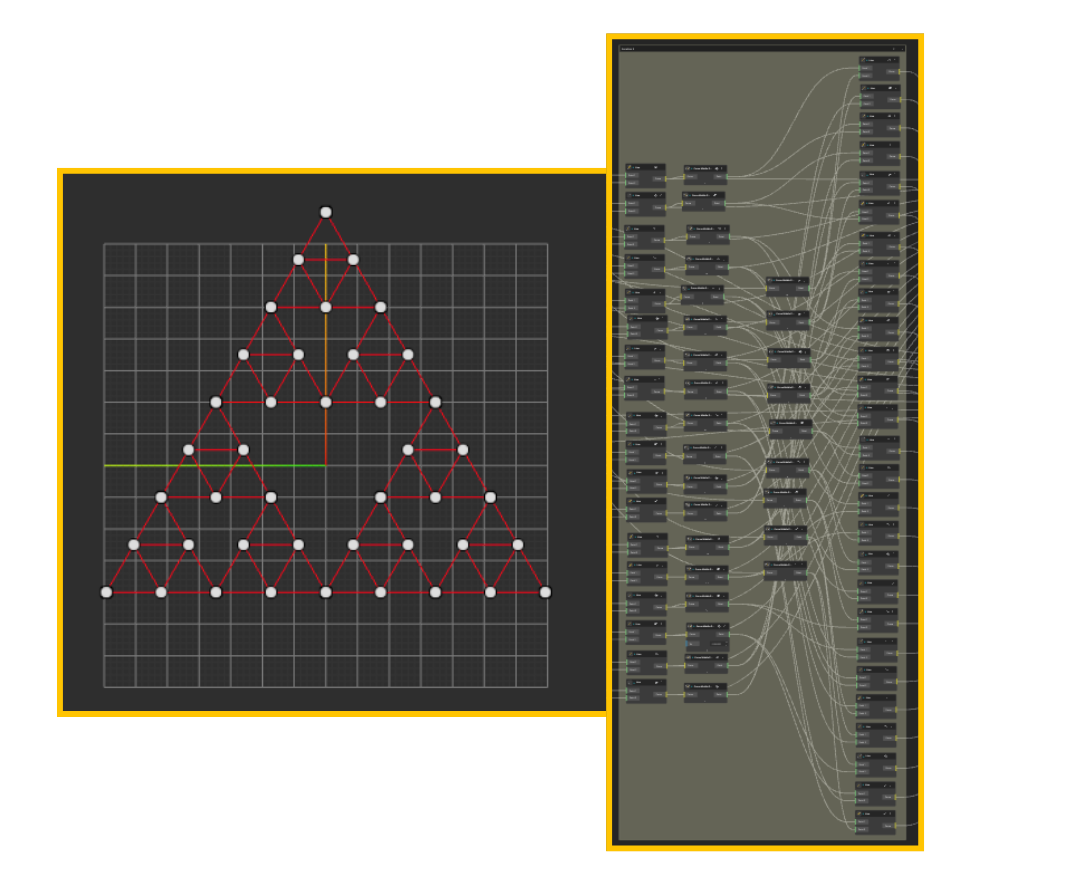

Step 5: Visual Adjustments and Orientation

Once the fractal geometry is complete:

-

A Rotate node is used to orient the final structure

-

Apply Material assigns surface properties

-

A Color Picker controls color independently

These steps do not affect the fractal logic.

They exist purely for visualization and presentation.

This separation between logic and appearance is intentional and important.

Why This Workflow Works Well

This approach avoids abstract repetition nodes and instead focuses on:

-

Explicit geometric construction

-

Clear cause-and-effect relationships

-

Full control at every iteration

It is especially useful when:

-

Learning how fractals are built

-

Teaching parametric logic

-

Debugging complex geometries

You can always add more iterations by copying the iteration group and reusing the same logic.

Limitations of the Node-Based Approach

While node-based workflows are intuitive, they do not scale well for complex fractal systems.

As iteration depth increases, the node graph grows rapidly, making it harder to read and manage. Repeating the same logic often requires duplicating large node groups, which makes updates error-prone and time-consuming.

Fractals also rely heavily on list structures. At higher complexity, list management can become fragile, and debugging list-related issues can distract from the design intent.

Because of these limitations, node-based workflows are best suited for learning, visual exploration, and low-depth fractals, rather than scalable or reusable systems.

Method 2: Creating Fractals Using TypeScript

While nodes are visual, fractals are fundamentally algorithmic. This is where TypeScript becomes powerful.

Instead of visually duplicating logic, you describe the behavior of the geometry in code. The result is often cleaner, more scalable, and easier to reuse.

Thinking in Algorithms

Most fractal scripts follow a simple structure:

- Define the base geometry

- Define how it transforms

- Repeat the transformation for a set number of iterations

- Store and return the generated geometry

Loops or recursive functions replace visual duplication. The logic stays compact even as complexity increases.

Control and Precision

TypeScript gives you:

- Exact control over iteration counts

- Mathematical precision

- Cleaner handling of large datasets

- Reusable and modular logic

This is especially useful when fractals are part of a larger system or need to be adjusted programmatically.

When TypeScript Is the Better Tool

TypeScript becomes the better choice when:

- Iteration counts are high

- Logic becomes hard to manage visually

- You want reusable fractal generators

- Performance and structure matter

Instead of fighting node complexity, you let code handle repetition.

Nodes vs TypeScript: Not a Competition

It is tempting to treat nodes and TypeScript as opposing approaches, but in practice they work best together.

Nodes help you understand and explore.

TypeScript helps you formalize and scale.

A common workflow is:

- Explore the fractal logic visually using nodes

- Understand how the geometry behaves

- Rebuild the logic in TypeScript for clarity and reuse

- Use nodes again for visualization and presentation

This hybrid approach mirrors how many professional computational design workflows operate.

Fractals as a Gateway to Parametric Thinking

Learning fractals is not about making abstract art alone. It is about training yourself to think in systems, rules, and iterations.

Once you are comfortable with fractals in BeeGraphy, you will find it easier to:

- Build parametric objects

- Create generative patterns

- Design adaptive systems

- Transition between visual logic and code

At that point, you are no longer just modeling geometry. You are designing processes.

Conclusion

Fractals show how complex 3D forms can emerge from simple, repeatable rules. Instead of manually modeling detail, we define a base geometry and let iteration do the work. This approach aligns naturally with parametric and computational design thinking.

Using BeeGraphy with TypeScript allows these ideas to scale cleanly. Logic stays explicit, iterations remain controllable, and geometry evolves in a predictable yet expressive way. More importantly, it encourages designers to think in systems rather than isolated shapes.

Once this mindset clicks, fractals stop being abstract mathematics and start becoming practical design tools. The same principles used here can extend to architectural systems, product structures, and generative visual experiments.